Dublin Core

Title

Description

The United States has a long history of limiting immigration and managing migrants once they are here, including a campaign to register non-citizen immigrants living in Utah.

Imagine you're a non-citizen living in Utah. When you open up your local newspaper after a long day at work, you find out that the federal government wants to register you as a potential threat to national security. According to the newspaper, you'll need to report to the nearest post office, where you'll complete a questionnaire and then be fingerprinted. At the post office, you're told that after a few weeks you'll get a registration card in the mail and your fingerprints will be sent to the FBI. This may sound like a modern-day plan to root out anti-American terrorists, but it's not.

The plan was actually part of the Alien Registration Act of 1940, in which more than 3 million people were expected to register with the government between August and December of that year. So-called "loyal aliens" were assured that their information would be kept secret, and that the only people who need fear were criminals and spies. The United States was still a year away from entering World War II, but many politicians were already jumpy about what they believed were potential threats coming from foreign-born immigrants.

Bingham Canyon was the Utah center for the registration effort. All non-citizens 14 years old and up were required to register in person. They were obliged to give details about their foreign military service, how they entered the country, what their occupation was, and the clubs they belonged to. They were also to provide a list of their relatives living in the United States. Those who ignored the government's order faced $1,000 fine and six months in jail.

Only two cases were prosecuted under the Alien Registration Act during World War II. In later years, however, the law was used to silence communists, socialists, and fascists. In 1957, the US Supreme Court declared some of its provisions were unconstitutional. But the law is still on the books.

Creator

Brandon Johnson of Utah Humanities © 2014

Source

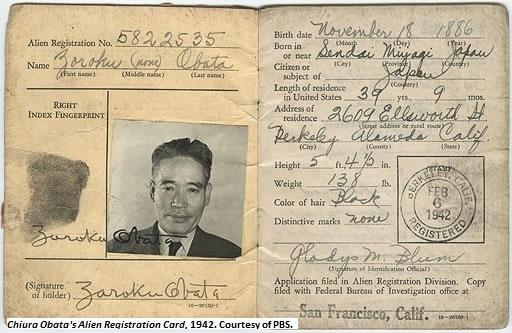

Image: Chiura Obata's Alien Registration Card, 1942. Obata and his family were removed from their home in the San Francisco area to an internment camp at Topaz, Utah, during World War II. Friends had pleaded with the government to let him be confined, if necessary, to his beloved Yosemite National Park, but the request was denied. Courtesy of PBS.

_______________

The Alien Registration Act of 1940 (also known as the Smith Act) made it illegal for anyone in the United States to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government, and required all alien residents in the United States over 14 years of age to file a comprehensive statement of their personal and occupational status and a record of their political beliefs. The text (in its amended form) can be found at http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/2385; See news reports about the Alien Registration Act of 1940 in the August 22, 1940, August 29, 1940, and November 28, 1940 editions of the Murray Eagle, all available at http://digitalnewspapers.org; Deanne S. Puloka, “The Alien Registration Act of 1940,” McKendree University Journal of Undergraduate Research, Issue 13, Summer 2009, accessed http://www.mckendree.edu/academics/scholars/issue13/puloka.htm; Elizabeth Burnes and Marisa Louie, “The A-Files: Finding Your Immigrant Ancestors,” Prologue Magazine of the National Archives, Spring 2013, accessed at http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2013/spring/a-files.pdf; Alien Registration forms on microfilm from 1940-1944 may be found at the Department of Homeland Security Citizenship and Immigration Services http://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/genealogy/alien-registration-forms-microfilm-1940-1944

Publisher

The Beehive Archive is a production of Utah Humanities. Find sources and the whole collection of past episodes at www.utahhumanities.org