Dublin Core

Title

Description

They say a picture is worth a thousand words... Artists got people moving West by idealizing both the journey and the destination.

The mapmaker for the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition, Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, created the first known map of Utah in 1776. Miera combined Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake into one large body of water with a river outlet that led straight to the nearby Pacific Ocean. For the next hundred years, artists on survey expeditions to Utah would continue to combine observation and imagination in their depictions of the Western landscape.

The earliest surveyors were looking for natural resources to tap and easier routes for settlers. The 1849 Stansbury Expedition was the first scientific team to use artists to document the flora, fauna, and geography of the Great Salt Lake. Soon after, the 1853 Fremont Expedition brought along photographer Solomon Carvalho to document a route through the Wasatch Mountains. Brigham Young also commissioned depictions of Utah to encourage immigration. At Young’s behest, English artist Frederick Piercy spent six months in Utah in 1853 creating drawings that appear in a guide for Mormon converts traveling to Salt Lake. Despite the guide's purpose, Piercy himself returned to England and was excommunicated for refusing to immigrate.

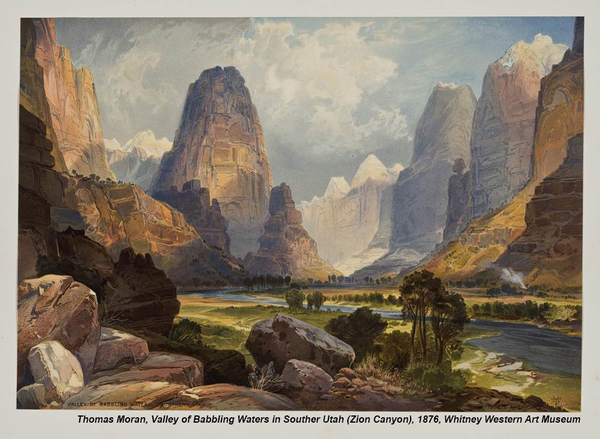

Many artists and photographers of the West exaggerated the wild landscape, emphasizing the vastness of the sky and the wonders of creation, in order to fuel the imagination and, more importantly, the immigration of people from the East. Some artists romanticized the journey, making trails look lush, exciting, even easy. Albert Bierstadt, for example, came to Utah with the 1859 Lander Expedition. Bierstadt was known for his sweeping mountain vistas, which convey the emotions provoked by nature more than they depict geographic reality. Other artists, like Thomas Moran, who accompanied the 1873 Powell Survey of the Colorado River, created paintings of Zion, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon that influenced Congress to protect these areas as wilderness.

Artistic license? Perhaps... But these expeditions produced an unparalleled body of artwork – drawings, paintings, and photographs – that contributed to the settlement of the West, and to its enduring mystique.

Creator

Michelle Hill for Utah Humanities © 2014

Source

Image: Thomas Moran, Valley of Babbling Waters in Southern Utah (Zion Canyon), chromolithograph on wove paper, 1876. Courtesy of the Whitney Western Art Museum.

_______________

See Richard H. Jackson, “Great Salt Lake and Great Salt Lake City: American Curiosities,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 2, Spring 1986, pp 128-147; Brigham D. Madsen, “Stansbury's Expedition to the Great Salt Lake, 1849-50,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 2, Spring 1986, pp 148-159; Wilford Hill Lecheminant, “'Entitled to Be Called an Artist': Landscape and Portrait Painter Frederick Piercy,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 1, Winter 1980, pp 49-65; Robert S. Olpin, Ann W. Orton, and Thomas F. Rugh, Painters of the Wasatch Mountains, Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2005, pp 6-45; Nick Scrattish, “The Modern Discovery, Popularization and Early Development of Bryce Canyon, Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 4, Fall 1981, pp 348-362; Mary Lee Spence, “The Fremonts and Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 3, Summer 1976, pp 286-302; Patricia Trenton and Peter H. Hassrick, The Rocky Mountains: A Vision for Artists in the Nineteenth Century, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983.

Publisher

The Beehive Archive is a production of Utah Humanities. Find sources and the whole collection of past episodes at www.utahhumanities.org

Date

2015-01-02