Dublin Core

Title

Description

As author Mark Twain brings Huckleberry Finn’s story to a close, we read as Huck “lights out for the territories” to find freedom out West, and imagine him riding into the sunset bouncing gamely from one job to another. But if Twain had continued Huck’s story – and done so honestly – he would have described run-ins with the agents who exploited the West’s volatile labor markets. These agents – or padrones, as they came to be known – did not encourage freedom. They stifled it for economic gain.

Utah’s most infamous padrone was a Greek man named Leonidas Skliris. Skliris started work for the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad shuttling Greek laborers wherever the company needed them. If the work got too dangerous or went underpaid, the workers quit and moved on to the next job. But between 1904 and 1912, Skliris curbed worker mobility by expanding his operations to include multiple industries and blacklisting workers who didn’t fall into line. Companies went to Skliris to contract labor. He, in turn, reduced their turnover rate by ensuring that, if you were Greek, and you wanted work, his was the only game in town.

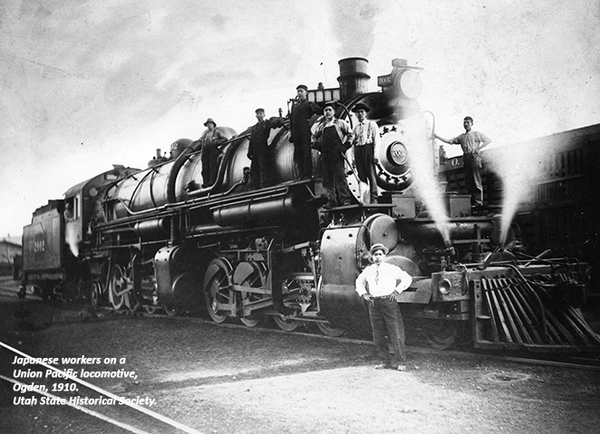

Other Italian and Japanese padrones implemented similar strategies. They made their money by demanding a fee upfront for finding someone work, and then extracting a portion from every paycheck that worker earned. The resulting transnational network of labor relations extended so far as to connect demand for miners in Bingham Canyon, for example, with economic hardships unfolding in Greece, Italy, and Japan.

In 1911, Greek workers appealed to the governor of Utah to free them from the padrone system. They asked Governor Spry, “Where are we? In the free country of Amerika or in a country dominated by a despotic form of government?” Out here on the Western Frontier, they experienced a more ruthless side of the American Dream, where even adventurers like Huck Finn probably sacrificed adventure in favor of survival.

Creator

Source

Image: Japanese workers on a Union Pacific locomotive, Ogden, 1910. Utaro Kariya (front) was the personnel manager who helped provide jobs for the 400 Japanese immigrants who labored on the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads. Utah State Historical Society.

_______________

See Gunther Peck, Re-Inventing Free Labor: Padrones and Immigrant Workers in the North American West, 1880-1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000 ), pp. 31-38, 49-69; Helen Papanikolas, “Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 38 (Spring 1970); Gunther Peck, “Padrones and Protest: ‘Old’ Radicals and ‘New’ Immigrants in Bingham, Utah, 1905-1912,” Western Historical Quarterly 24 (May 1993), pp. 157-178; A. Kent Powell, The Next Time We Strike: Labor in Utah’s Coal Fields, 1900-1933 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1985), pp. 84-92; Jeffrey D. Nichols, “The Fall of Skliris, 'Czar of the Greeks',” History Blazer, December 1996.