Dublin Core

Title

Description

Learn about Utah’s nineteenth century midwives, who were unusual in that they were actually paid for their work as medical providers.

Much of the work that sustained Utah’s communities in the late nineteenth century was done by women, in the home, for no wage. But those women who worked for wages outside their homes often did so in professions such as midwifery, where few would question a woman earning money to help other women give birth.

One such woman was Hannah Sorensen, a 60-year-old Danish Mormon immigrant, who moved to Bluff in 1896 to serve as a paid midwife for southeastern Utah. Driven by faith and a holistic approach to medicine, Sorensen not only delivered babies but also served as the “doctor, the obstetrician, [and] the all-round physician for disorders [both] physical and mental.” Sorensen could start the day mending broken bones and end it with administering folk remedies. When she delivered a baby, she either stayed with the mother for her ten-day confinement or visited daily to help cook, clean, care for the newborn, and take charge of the other children.

It might be easy to think that midwives chose their occupation based on some “natural instinct” or sense of devotion. But midwifery was one of the few jobs in nineteenth century Utah open to women who wanted to earn a wage. Hundreds of women who received training in Salt Lake City took up midwife positions across the state, and charged between $2 and $10 for a delivery. The wages they earned – and the demand for their specialized skills – afforded midwives more autonomy than many women had at the time.

Nonetheless, midwives were not free from expectations consistently faced by women in the workplace. When Hannah Sorensen trained other midwives, for example, she advised them to remain “refined, quiet, and sensitive” so as to not jeopardize their place as “a true lady.” Another trainer, Dr. Ellis Shipp, insisted that midwives be pleasant, clean, and good cooks who could “communicate another’s thoughts and actions” without coming across as “too talkative.”

Still, with their careful break from tradition, Utah midwives both served their communities and opened up new possibilities for women and their work.

Creator

Source

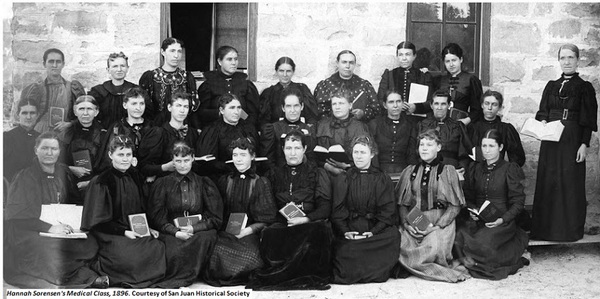

Image: Hannah Sorensen’s medical class, 1896. Midwives like Hannah Sorensen (right) were unusual because they were paid for their work as medical providers. Sorensen passed on her skills and trained classes of future midwives in medicine and obstetrics. Image courtesy San Juan County Historical Society.

_______________

See Robert S. McPherson and Mary Lou Mueller, “Divine Duty: Hannah Sorensen and Midwifery in Southeastern Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 65, no. 4 (1997), pp. 335-355.