Dublin Core

Title

Raising Hopes and Oysters in Great Salt Lake

Description

Have you ever looked out over Great Salt Lake and thought, “I’d really like to grow oysters there?” You probably haven’t. Learn how Utahns have tried — and failed — to cultivate this unlikely product.

The Mountain West is not known for its seafood. But that did not stop Utahns from trying — several times over seven decades — to cultivate oysters in Great Salt Lake.

It started when white settlers in the Salt Lake Valley imagined the desert blossoming as the rose. This vision included turning Great Salt Lake into a site for aquaculture. In 1853, an opinion column in the Deseret News recommended raising oysters by simply directing the appropriate amount of fresh water into a portion of the salty lake. The author envisioned not just oysters, but “clam, crab and lobster,” and even salmon and shad.

It turns out that the prospect of oysters in the lake was more than just idle speculation. In 1882, an entrepreneur in Corinne went so far as to buy 600 oyster seedlings. In 1898, an expert from the US Fisheries Service spent three weeks investigating the Jordan, Weber, and Bear River Bays for the possibility of raising oysters, but decided the idea was not commercially viable. This early round of experiments failed due to high levels of mud flowing in from the rivers, not to mention the highly variable levels of salt in the water.

Still, some Utahns entertained this possibility into the twentieth century. In 1917, R.H. Siddoway, who was Utah’s Fish and Game commissioner, investigated Bear River Bay for its oyster-raising potential. Siddoway hoped that the new Lucin Cutoff — a causeway through Great Salt Lake completed in 1904 — had freshened the water enough to be favorable for oysters. The salinity tests were encouraging, and Siddoway felt so optimistic that he made plans to introduce oyster seed into the waters. But the results — again — were unfavorable.

So, do these oyster experiments reflect a hardy resourcefulness, or just a refusal to accept the constraints of our natural environment? For better or worse, Utahns have long tried to make a living — or money — or both — by bending nature to human will.

The Mountain West is not known for its seafood. But that did not stop Utahns from trying — several times over seven decades — to cultivate oysters in Great Salt Lake.

It started when white settlers in the Salt Lake Valley imagined the desert blossoming as the rose. This vision included turning Great Salt Lake into a site for aquaculture. In 1853, an opinion column in the Deseret News recommended raising oysters by simply directing the appropriate amount of fresh water into a portion of the salty lake. The author envisioned not just oysters, but “clam, crab and lobster,” and even salmon and shad.

It turns out that the prospect of oysters in the lake was more than just idle speculation. In 1882, an entrepreneur in Corinne went so far as to buy 600 oyster seedlings. In 1898, an expert from the US Fisheries Service spent three weeks investigating the Jordan, Weber, and Bear River Bays for the possibility of raising oysters, but decided the idea was not commercially viable. This early round of experiments failed due to high levels of mud flowing in from the rivers, not to mention the highly variable levels of salt in the water.

Still, some Utahns entertained this possibility into the twentieth century. In 1917, R.H. Siddoway, who was Utah’s Fish and Game commissioner, investigated Bear River Bay for its oyster-raising potential. Siddoway hoped that the new Lucin Cutoff — a causeway through Great Salt Lake completed in 1904 — had freshened the water enough to be favorable for oysters. The salinity tests were encouraging, and Siddoway felt so optimistic that he made plans to introduce oyster seed into the waters. But the results — again — were unfavorable.

So, do these oyster experiments reflect a hardy resourcefulness, or just a refusal to accept the constraints of our natural environment? For better or worse, Utahns have long tried to make a living — or money — or both — by bending nature to human will.

Creator

Nate Housley for Utah Humanities © 2021

Source

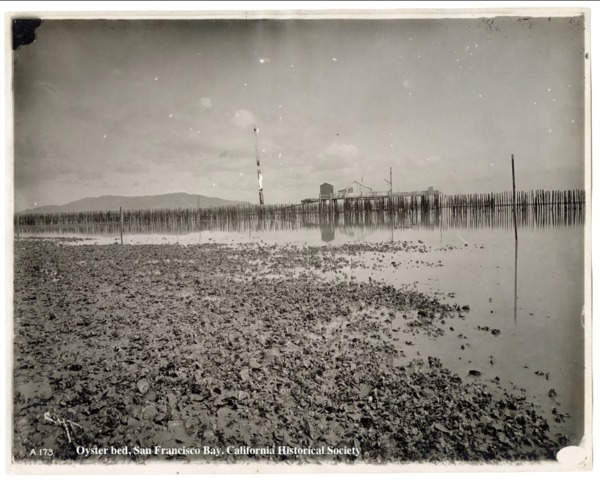

Image: An example of a more conventional, successful oyster bed. "View of oyster bed at low tide," San Francisco Bay, California, General Subjects Photography Collection, PC--GS--Industry--Fishing--Oysters, California Historical Society, PC-GS_00590

_______________

See “Oysters in the Shell,” Deseret News, Feb 5, 1853; “Oysters. A Failure Predicted About their Growth in Great Salt Lake,” Salt Lake Herald Republican, Aug 17, 1882; “Oysters in the Great Salt Lake,” Deseret News, Aug 23, 1882; Report of the Fish and Game Commissioner of the State of Utah, 1897–1898, Salt Lake City: 20; Report of the Fish and Game Commissioner of the State of Utah, 1917–1918, Salt Lake City: 15; “Can oysters be grown in the Great Salt Lake may find an answer in an old experiment,” Ogden Daily Standard, Dec 24, 1918; US Geological Service,Great Salt Lake Utah, Water-Resources Investigations Report 1999–4189, April 2007.

_______________

See “Oysters in the Shell,” Deseret News, Feb 5, 1853; “Oysters. A Failure Predicted About their Growth in Great Salt Lake,” Salt Lake Herald Republican, Aug 17, 1882; “Oysters in the Great Salt Lake,” Deseret News, Aug 23, 1882; Report of the Fish and Game Commissioner of the State of Utah, 1897–1898, Salt Lake City: 20; Report of the Fish and Game Commissioner of the State of Utah, 1917–1918, Salt Lake City: 15; “Can oysters be grown in the Great Salt Lake may find an answer in an old experiment,” Ogden Daily Standard, Dec 24, 1918; US Geological Service,Great Salt Lake Utah, Water-Resources Investigations Report 1999–4189, April 2007.

Publisher

The Beehive Archive is a production of Utah Humanities. Find sources and the whole collection of past episodes at www.utahhumanities.org/stories.

Date

2021-03-12