Dublin Core

Title

Description

Water, and how to control it, is an age-old consideration for the people of Utah. Over a thousand years ago, Utah’s earliest agriculturalists were the Fremont and Ancestral Puebloan peoples. Like modern farmers, they faced the problem of how to use Utah’s scarce freshwater to maximize their crops. Their strategies were different, but both groups survived and thrived in Utah’s arid landscape by adapting themselves to the land and its water.

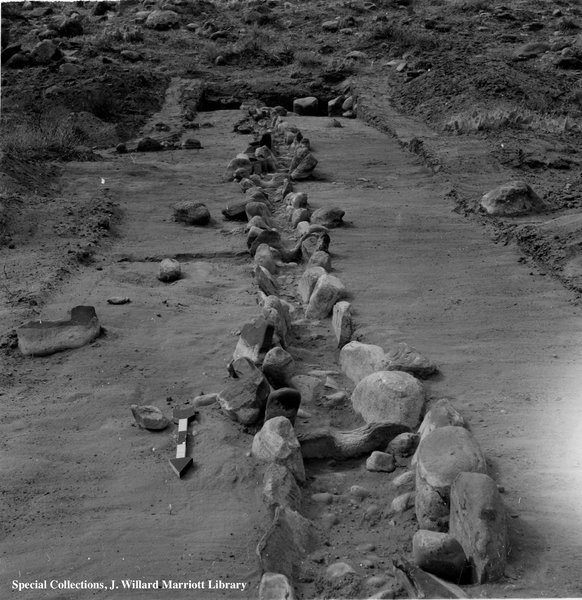

The Fremont peoples flourished in Utah north and west of the Colorado River from around 1,800 to 800 years ago. They supplemented their foraging with agriculture and grew the “three sisters” crops – corn, beans, and squash. Fremont peoples did manage water sources, but their farming motto seems to have been, “work smarter, not harder.” Instead of building elaborate canal systems, they exploited natural landforms such as slopes, drainages, and small streams to transport water to their fields. They also placed their gardens near seeps and in creek bottoms. Archaeological evidence shows that the Fremont also constructed irrigation ditches to water their crops. Although labor-intensive, these ditch systems led to a significant increase in crop production, ultimately allowing the Fremont to thrive in inhospitable landscapes.

Ancestral Puebloans lived in southeast Utah on the Colorado Plateau from approximately 1,400 to 700 years ago. The region had a notoriously variable climate during this period, making access to and control of water essential to survival. Ancestral Puebloans often built their towns around a spring or cistern. Archaeologists have also found evidence of earthen dams with pond sediments and reservoirs where farmers caught and stored rainwater and snowmelt. These structures demonstrate deliberate and successful manipulation of water in prehistory.

As the climate became slightly cooler and less dry near the end of the thirteenth century, the Fremont returned to hunting and gathering, as their ancestors had done for millennia. In Utah’s Four Corners area, many Ancestral Puebloans chose to emigrate south to continue raising crops in pueblos that still exist today in New Mexico and Arizona.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Larry V. Benson & Michael S. Berry, “Climate Change and Cultural Response in the Prehistoric American Southwest,” KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History 75 (2009): 87-117; Shannon Arnold Boomgarden, Experimental Maize Farming in Range Creek Canyon, Utah (PhD Dissertation 2015); Bruce Bradley, “Pitchers to Mugs: Chacoan Revival at Sand Canyon Pueblo” KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History 74 (2008): 247-262; Chimalis R. Kuehn, The Agricultural Economics of Fremont Irrigation: A Case Study From South-Central Utah (Thesis 2014); Duncan Metcalfe and Lisa Larrabee, “Fremont Irrigation: Evidence from Gooseberry Valley, Central Utah” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 7 (1985): 244-254; Steven R. Simms, Chimalis Kuehn, Nancy Kay Harrison, The Archaeology of Ancient Fremont Irrigation (2012 33rd Great Basin Anthropological Conference Poster); Richard K. Talbot and Lane D. Richens, Steinaker Gap OP #2: An Early Fremont Farmstead (BYU Press, 1996); Richard H. Wilshusen, Melissa J. Churchill and James M. Potter, “Prehistoric Reservoirs and Water Basins in the Mesa Verde Region: Intensification of Water Collection Strategies during the Great Pueblo Period,” American Antiquity 61 (1997): 664-681; Kenneth R. Wright, “Ancestral Puebloan Water Handling,” Lakeline (2008): 23-28.