Dublin Core

Title

Description

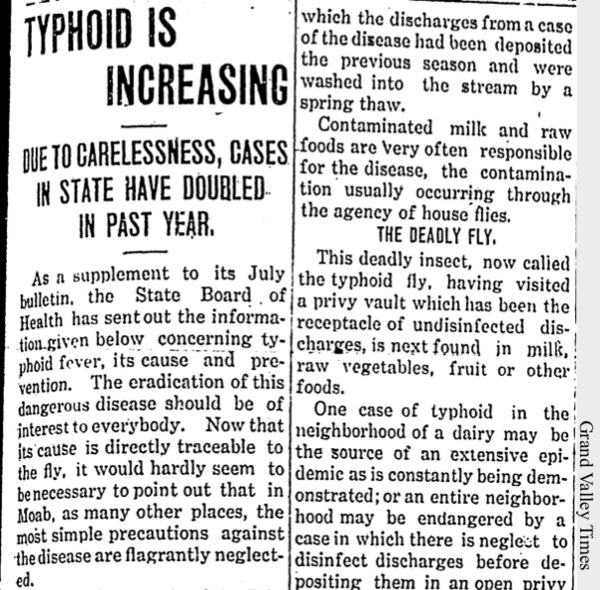

Shortly after Christmas in 1916, the Rawlins family of Cornish, Utah lost their twelve-year-old daughter Margarete to typhoid fever. Her unexpected death came just weeks after her younger brother succumbed to the same illness. The Rawlins’ story was tragic, but sadly, not unique. In the early 1900s, typhoid fever circulated through Utah communities, with 2,028 cases of the disease reported in the first fifteen years of the century. By this time, it was widely understood that the infectious typhoid bacteria spread through contaminated water. If only city officials would upgrade their public water systems!

Typhoid is easily passed along when an infected person handles food without properly washing their hands or cleans food storage containers with contaminated water. A symptomless carrier can infect an unsuspecting victim, causing fever and often death. Newspapers at the time printed practical tips on avoiding infection, such as boiling water before use, and attempted to dispel misinformation about germs and bacteria.

As an entirely preventable disease, public health experts encouraged individual responsibility but also promoted improvements to city water infrastructure throughout the state. Pools of stagnant water, poor sewage treatment, and the proximity of animals to water sources all created the perfect environment for typhoid bacteria to thrive. As cities and towns grew, so did the risk for contamination and the threat of disease. For many Utahns who previously had access to clean, fresh water, typhoid was a scary side effect of urban development and growth.

Public demand for water purification systems intensified, and pressure mounted on cities to invest in facilities that would provide residents with reliably clean drinking water. Utah voters demanded more regulation and control over public health and community infrastructure. In response, cities began to distribute funds to develop better water systems, including improved sewer systems. They also passed stricter laws regarding food handling. By 1915, Salt Lake City instituted water and sewer purification programs, using chlorine to eradicate the bacteria from drinking water, which dramatically decreased typhoid cases. These efforts, in combination with a successful vaccination campaign, all but eradicated this nasty disease in Utah.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Melvin M. Owens, MBA and Suzanne Dandoy, M.D., M.P.H., “A History of Public Health in Utah,” Utah Department of Health; Plenk, Henry P. “Medicine in Utah.” Utah History Encyclopedia; “Young Girl Dies Suddenly of Typhoid Fever,” Logan Republican, December 30, 1916; “Typhoid Fever Facts,” Salt Lake Herald Republican, October 13, 1907;“Typhoid is Increasing,” Grand Valley Times, September 2, 1910; “Typhoid and Water,” Ogden Daily Standard, September 30, 1902; Miriam B. Murphy, “Salt Lake City Had its Typhoid Mary,” History Blazer, April 1996. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “History of Drinking Water Treatment,” Last modified November 26, 2012; Daugs, Donald. Utah Water: A Precious Resource. Salt Lake City: Utah Division of Water Resources, Department of Natural Resources, Utah State University, 1995.