Dublin Core

Title

Description

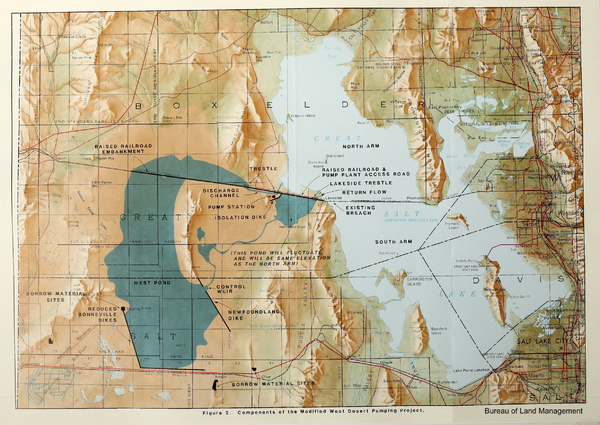

In the 1980’s, a flooding Great Salt Lake threatened transportation, industry, and the economy in Utah. Under the leadership of Utah governor Norm Bangerter, the emergency was solved by installing three huge pumps on the lake’s western shore that would pull water away from urban areas out to the desert to evaporate. After only two years of use, the pumps were moth-balled. Thirty years later, this $60 million project still sits out in the West Desert, waiting for another flood.

In 1982, after one of the strongest El Niño events ever recorded, Great Salt Lake was monitored for expected flooding. Starting late May of 1983 the massive snowpack melted fast and the lake rose around 20 feet, nearly doubling its surface area. I-80 was swamped, downtown Salt Lake was swamped, and in other areas of the state, entire mountainsides washed away. Great Salt Lake’s flooding during this period is estimated to have caused around $240 million in damages to roads, railroads, private property, and infrastructure such as sewage treatment plants.

The conversation in the Utah government under Scott Matheson quickly turned to finding a way to dominate nature’s natural cycles. Some people thought dying the lake a darker color would increase light absorption and speed up evaporation. One geologist proposed firing a nuclear bomb into the lake or West Desert, to create a crater the lake could then fill. Instead, under Bangerter’s governance in 1987, Utah installed three water pumps – 27 feet long, 17 feet tall, and each weighing 81 tons. They were a practical quick fix and were cheaper than other options that would need up to ten years to take effect. These pumps removed 1.3 million gallons of water per minute, feeding the water out into the West Desert. As for the environmental impact of this process, officials said “there's virtually nothing out there, maybe a few lizards and one or two rabbits.''

As expected, over the next two years the lake level lowered. The project won the Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award from the American Society of Civil Engineers. But, others noted the futility of creating a massive infrastructure project for a problem that now seems so temporary. With Utah’s waters diverted away from Great Salt Lake at an increasing rate to support our growing population, it is uncertain whether the pumps will ever be used again.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Genevieve Atwood and Don Mabey, transcript of an oral history conducted 2014 by Greg Smoak, Great Salt Lake Oral History Project U-3244, American West Center and J. Willard Marriott Library Special Collections Department University of Utah, 2014; Thomas J. Knudson, “Pumping is Begun to Create a Second Salt Lake,” The New York Times, April 11, 1987; “The Great Salt Lake West Desert Pumping Project It’s Design, Development and Operation,

Utah Division of Water Resources Utah Department of Natural Resources, June 1999; Bob Bernick Jr., “Remember Bangerter? Oh, The Pumps,” The Deseret News, Dec 13, 1992; John Hollenhorst, “Lake's pumps still high and dry,” The Deseret News, April 19, 2011.