Dublin Core

Title

Description

Utah’s hot springs have long been sought for their positive health benefits. Indigenous people regularly set up their winter homes near mineral springs for the healing waters and warmth. But when white settlers took control of the land in the mid-1800s, many communal springs were no longer publicly accessible. Businessmen saw an opportunity to profit from the natural elements on their newly-acquired properties, and an industry of “wellness” was born. Savvy landowners sold visitors access to nature, giving them a temporary escape from newly-developed urban environments and a miracle cure for modern ailments.

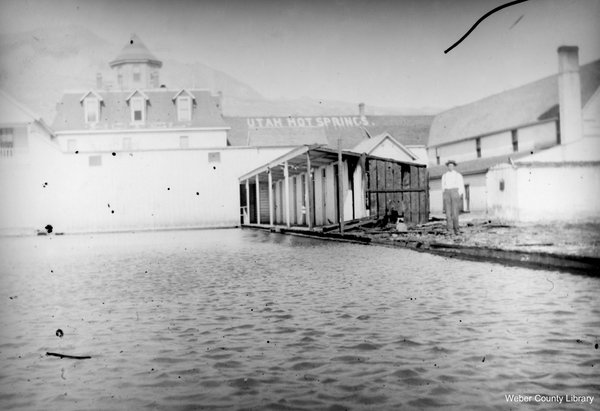

Relying on the warm waters to entice visitors, Dr. Rason Slater developed the Utah Hot Springs in 1880 at the mouth of Ogden Canyon. A small steam engine ran between the resort and downtown Ogden, making the eight mile trip an easy visit for many city dwellers. Popularity of the resort grew and within eight years, the destination boasted a hotel, saloon, dancehall, and commissary.

Dr. Slater published advertisements selling the mythical healing properties of mineral waters to anxious Utahns and monetized the recreational use of water. His newspaper ads promised that ailments such as rheumatism, asthma, syphilis, paralysis, nervous diseases, and -- as he called them -- “all of the peculiar complaints and disabilities to which females are subject,” could be cured by a warm sulfuric bath at his resort. Despite Dr. Slater’s claims, it is likely that the most beneficial result the resort encouraged was actual bathing.

Visitors to Utah Hot Springs escaped to the pools seeking cures for diseases that were often attributed to urban life. The close proximity of the resort to downtown Ogden offered those living in the city an easy day trip into nature. For a fee, urbanites could soak in the waters and forget about the uncertainty of a quickly developing urban environment. What was once a communal natural resource became a luxurious reminder of the healing properties of nature -- but only if you were able to pay for it.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Darrell E. Jones and W. Randall Dixon, “'It Was Very Warm and Smelt Very Bad': Warm Springs and the First Bath House in Salt Lake City,” Utah Historical Quarterly 76, no. 3 (Summer 2008), p 212; Richard C. Roberts and Richard W. Sadler, A History of Weber County, Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1997; Linda Thatcher, “Castilla Hot Springs,” Beehive History 7 (1981); Treleaven, Sarah. “The Enduring Appeal of Escapism: A History of Wellness Retreats.” Medium. April 16, 2019; Utah Historical Society, “Utah’s Interurbans: Predecessors to the Light Rail,” The History Blazer, December 1995.