Dublin Core

Title

Description

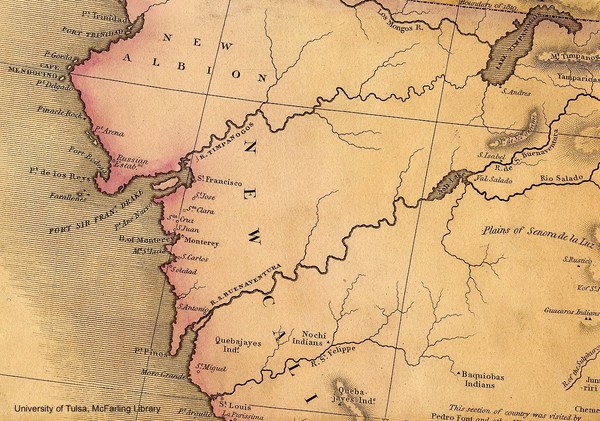

From the 1770s to the 1840s, a majority of explorers, politicians, and white settlers firmly believed in a great “river of the West” that ran from Utah all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Despite never laying eyes on this legendary river, mapmakers recorded it this way for nearly 70 years. They were convinced the land would provide an easy coast-to-coast waterway – making Manifest Destiny all the more possible.

What led to this kind of wishful thinking? A twisted game of telephone began in 1776 when two Franciscan monks tried to find a new route between Spanish colonies in New Mexico and California. When the Ute people at Utah Lake described to them a nearby river that flowed to a salty body of water, the mapmaker traveling with the monks probably assumed they meant the sea instead of Great Salt Lake. A waterway flowing to the sea would have made Utah an ideal colony for the Spanish Empire. Nineteenth century mapmakers later consulted these Spanish maps to make their own, and suddenly even the U.S. military under President Thomas Jefferson believed in a river connecting Utah Lake to the ocean. This river was recorded with the same name the Spanish had given it: the Rio Buenaventura, meaning "river of good fortune."

It wasn’t until American explorer John C. Fremont surveyed Utah’s landscape in the 1840s that Americans learned there was no Western Mississippi that flowed to the sea. Fremont rightly realized that Utah is part of a Great Basin, where water collects and pools in terminal lakes. Even then, when Fremont explained his discovery to U.S. President James Polk in 1845, Polk didn’t believe him. He told Fremont he was an impulsive young man and remained certain that outlets flowed from the Rockies to California – after all, it was on the map!

How could the president persist in his belief, despite evidence confirming a waterway could never be possible? Put simply, Manifest Destiny and westward expansion required a lot of money. For policy makers and the public, imagining Utah as a bountiful paradise – and not an arid, isolated desert – made colonizing America a lot less daunting.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Richard V. Francaviglia, Mapping and Imagination in the Great Basin: A Cartographic History (Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press, 2005); John L. Kessell, Whither the Waters: Mapping the Great Basin, from Bernardo de Miera to John C. Frémont (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2017); John Charles Frémont, Memoirs of My Life, vol. 1 (Chicago: Belford, Clarke & Company, 1887): 418-419.