Dublin Core

Title

Description

Water normally means life for farmers and their crops. But in the early 1900s, when smelters in the Salt Lake Valley were processing 6,000 tons of ore per day, their gas emissions caused deadly acid rain. Farmers fought the smelting companies to protect their crops, but with few regulations on toxic emissions, they were at a disadvantage.

Acid rain occurs when sulfur dioxide gas from smokestacks reacts with moisture in the air and rains down, bleaching plants and poisoning animals. In 1904, Salt Lake Valley farmers sued the American Smelting and Refining Company -- known as “ASARCO” -- for damages from the rain. Some smelters relocated or installed rudimentary filtration systems, but farmers remained convinced that acid rain still damaged their crops. In response, ASARCO and other companies established their own farms near their smelters and hired teams of botanists to research the problem. The scientists conducted over 3500 experiments in 1915 alone, and discovered other important factors that led to crop failure, such as temperature and humidity. Armed with their scientific methods, smelters farmed successfully. One company even took its crops to the 1917 Utah State Fair, showcasing barley, corn, and dairy products all grown in the shadow of its smokestacks.

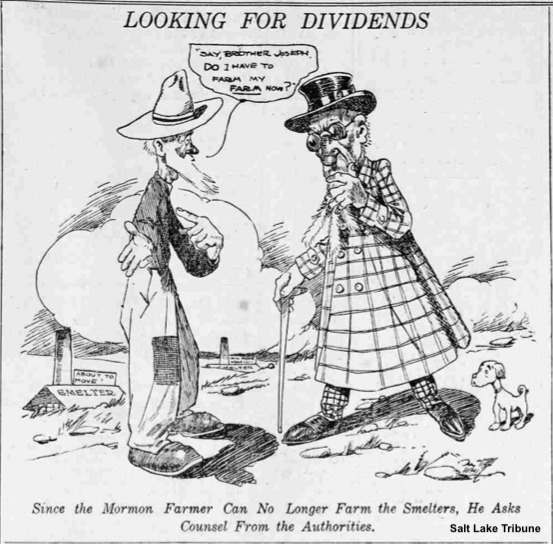

These bushels of visibly unaffected produce undermined the authority of local farmers, who did not have the benefit of new technologies or teams of scientists. Farmers hoping to receive compensation for damages from continued acid rain were often portrayed by company lawyers as simply bad at their jobs. Newspapers called them “smoke farmers” who blamed every issue on nearby smelters just to make a buck. Anti-farmer sentiment rose after more than 400 farmers won their court case against ASARCO and four other companies, which shut down all but one smelter in the Valley and cost hundreds of local jobs.

Still, some good came from the war over acid rain in Salt Lake Valley: company farming near smelters helped researchers discover better agricultural technologies, and the Utah Agricultural College -- now Utah State University -- expanded its research field stations. Yet, it would not be until the 1960s Clean Air Act that sulfur dioxide emissions began to be reined in.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Michael A. Church, “Smoke Farming: Smelting and Agricultural Reform in Utah, 1900-1945,” Utah Historical Quarterly 72, no. 3 (2004); “Looking for Dividends,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 28, 1906, Utah Digital Newspapers, accessed June 2022; Jeffrey D. Nichols, “The Salt Lake Valley Smelter War,” History Blazer, April 1995; John E. Lamborn and Charles S. Peterson, “The Substance of the Land: Agriculture v. Industry is the Smelter Cases of 1904 and 1906,” Utah Historical Quarterly 53 no. 4 (1985).