Dublin Core

Title

Description

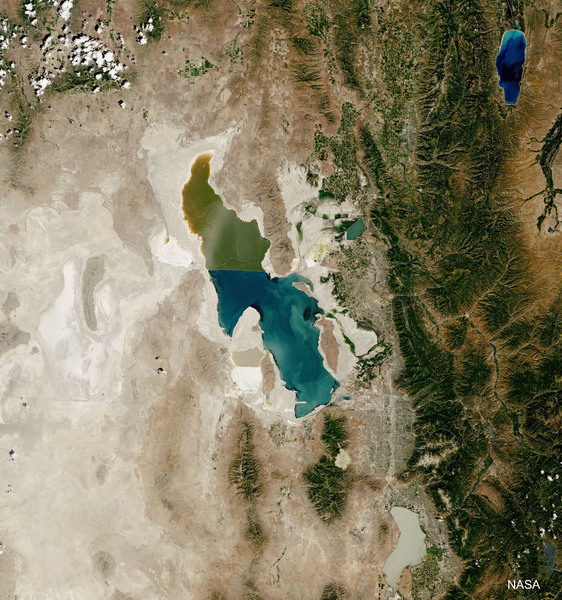

Utah is literally split down the middle when it comes to water – the Great Basin watershed lies to the west and the Colorado River Basin to the east. Even before this place was called Utah, the scarcity of water has always required us to negotiate with the land and with each other.

The value of water, for example, depends on the eye of the beholder. Utah’s recreation industry relies on river-carved canyons, wild rapids, and our famous powder snow. Yet what we now recognize as natural treasures did not seem particularly valuable to early settlers. In their attempts to harness water for agriculture, redrock canyons prone to flooding were obstacles, not assets.

And who controls water? Our extensive system of dams were constructed for storage and hydropower by the federal government. In the 1960s, Utah Governor Dewey Clyde sought to wrest control from the feds by channeling public hydropower through a local, private utility. But the government had borne the costs of building the dams and, accordingly, wanted to collect the revenue. Governor Clyde faced a formidable opponent in Floyd Dominy, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, who won the day. The federal government continues to supply public hydropower to Utahns.

Dams in Utah have also provoked nature lovers. In the 1950s, the burgeoning environmental movement drew national attention to Utah’s scenic canyons and wildlife as dam-builders proposed to inundate them. The perception of environmentalists as outsiders led to clashes between rural and urban water users. But not all environmentalists are city-dwellers. It was local duck hunters, after all, who scored one of the state’s biggest conservation wins by helping establish the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.

The story of water in Utah is one of conflict, certainly, but also adaptation. Agricultural expert and LDS apostle John Widtsoe proclaimed in 1928, “The destiny of the earth is to be subject to man.” While many have wished for this to be true, the history of our state seems to demonstrate that water always has the last word. As long as humans continue to live here, we will need to find a way to get along with Mother Nature.

Creator

Source

______________

See Paul W. Reeve, “A Little Oasis in the Desert: Community Building in Hurricane, Utah, 1860-1920.” Utah Historical Quarterly 62 no. 3 (Summer 1994); Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water (New York: Penguin, 1986); Craig W. Fuller, Robert E. Parson, and F. Ross Peterson, eds., Water, Agriculture, and Urban Growth: A History of the Central Utah Project (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 2016); Fisher Sanford Harris, “100 Years of Water Development” (a report submitted to the board of directors of the Metropolitan Water District of Salt Lake City, the board of commissioners of Salt Lake City Corporation, and to the citizens of Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City, UT, April 1942); Jack Ray, Duck Fever: Hunting Clubs and the Preservation of Marshlands on the Great Salt Lake, Utah Historical Quarterly 87 no 1 (2019); John A. Widtsoe, Success on Irrigation Projects (New York: Wiley & Sons, 1928); Gregory E. Smoak, “Every History Has a Nature: Thoughts on Doing Public Environmental History,” The Public Historian 44 no 3 (August 2022), pp 9-23.