Dublin Core

Title

The Meeker Incident: Allotment & Dispossession of Ute Land

Description

A federal agent in Colorado tried to force a band of Utes to take up farming. This would come to impact not just Utes in Utah, but national Indian policy.

The experience of the Ute people was a crucial factor in the development of national policies about Native land use, and it all started with one unfortunate incident in White River, Colorado. As Utah’s Utes were being relocated to the Uinta Basin, many other Ute bands remained in their western Colorado homelands, where they too faced pressure to assimilate. In 1878, an overzealous federal agent named Nathan Meeker was sent to the White River Utes to influence them to take up agricultural work. But the Utes had no interest in becoming farmers.

Meeker’s heavy-handed actions -- including plowing up the ground that the Utes used for horse racing -- led to growing conflict. After a physical confrontation, Meeker called in the military. The result was a panic among the Utes, a pitched battle where Ute warriors pinned down the federal troops, and the death of Meeker and ten other agency employees. This so-called “Meeker Incident” became the central justification for the removal of the White River and Uncompaghre Utes to the arid Uinta Basin. But it also had lasting echoes in national policy. Congress started to debate what to do about tribal relations, first passing a Ute Removal Bill which forced the White Rivers and Uncompaghres to move to the Uintah Reservation. The bill also provided a model for the 1887 Dawes General Allotment Act, which made the division of Native land into private lots national policy.

While the idea of allotment found general support in Congress, opponents predicted it would only result in dispossession of Native land. They proved correct. The Utes did their best to stave off allotment, but in 1905 the process was forced upon them. Once the initial distribution of land to the Utes was complete, most of what remained was deemed “surplus” and opened to white settlers, who flooded into the Basin, founding the towns of Roosevelt, Myton, and Ballard.

A number of Utes did turn to farming, but largely the people rejected what was an alien way of life. On the Uintah and Ouray Reservation -- as with every other reservation where the program was implemented -- allotment failed to fully assimilate Native people, but succeeded in dispossessing them of their land.

The experience of the Ute people was a crucial factor in the development of national policies about Native land use, and it all started with one unfortunate incident in White River, Colorado. As Utah’s Utes were being relocated to the Uinta Basin, many other Ute bands remained in their western Colorado homelands, where they too faced pressure to assimilate. In 1878, an overzealous federal agent named Nathan Meeker was sent to the White River Utes to influence them to take up agricultural work. But the Utes had no interest in becoming farmers.

Meeker’s heavy-handed actions -- including plowing up the ground that the Utes used for horse racing -- led to growing conflict. After a physical confrontation, Meeker called in the military. The result was a panic among the Utes, a pitched battle where Ute warriors pinned down the federal troops, and the death of Meeker and ten other agency employees. This so-called “Meeker Incident” became the central justification for the removal of the White River and Uncompaghre Utes to the arid Uinta Basin. But it also had lasting echoes in national policy. Congress started to debate what to do about tribal relations, first passing a Ute Removal Bill which forced the White Rivers and Uncompaghres to move to the Uintah Reservation. The bill also provided a model for the 1887 Dawes General Allotment Act, which made the division of Native land into private lots national policy.

While the idea of allotment found general support in Congress, opponents predicted it would only result in dispossession of Native land. They proved correct. The Utes did their best to stave off allotment, but in 1905 the process was forced upon them. Once the initial distribution of land to the Utes was complete, most of what remained was deemed “surplus” and opened to white settlers, who flooded into the Basin, founding the towns of Roosevelt, Myton, and Ballard.

A number of Utes did turn to farming, but largely the people rejected what was an alien way of life. On the Uintah and Ouray Reservation -- as with every other reservation where the program was implemented -- allotment failed to fully assimilate Native people, but succeeded in dispossessing them of their land.

Creator

By Greg Smoak for Utah Humanities © 2023

Source

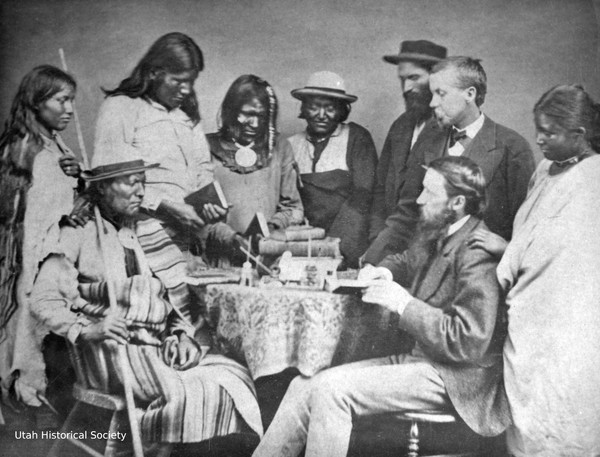

Image: Ute leaders meeting with Colonel William Frederick Milton Arny, 1867. As Utah’s tribes met with government officials, many did not realize that the reservation system would require their permanent confinement and assimilation. The reality of allotment was devastating for Native communities in Utah. The ceremonies, nomadism, seasonal practices, and environments so important to many of these Native communities were forever changed because of private land allotment. Image courtesy Utah Historical Society.

_______________

See Sondra Jones, Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People (University of Utah, 2019); Greg Smoak, Nate Housley, and Megan Weiss, Rural Utah at a Crossroads (Utah Humanities, 2023); Forrest Cuch, A History of Utah’s American Indians (Utah State University Press, 2003).

_______________

See Sondra Jones, Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People (University of Utah, 2019); Greg Smoak, Nate Housley, and Megan Weiss, Rural Utah at a Crossroads (Utah Humanities, 2023); Forrest Cuch, A History of Utah’s American Indians (Utah State University Press, 2003).

Publisher

The Beehive Archive is a production of Utah Humanities. Find sources and the whole collection of past episodes at www.utahhumanities.org/stories.

Date

2023-12-18