Dublin Core

Title

Description

In August 1896, Mary Jones attended a class in Bluff, Utah, taught by a woman visiting from out of town. There was no ordinary instruction on mending or cooking -- instead Mary took detailed notes on how to set a broken bone with pressure, splints, and bandages soaked in cornstarch. During Mary’s lifetime, doctors were scarce in remote areas. Instead, midwives, armed with folk knowledge and practical skills, traveled across rural Utah to teach people how to deliver babies, as well as take care of everyday harms like rashes, snake bites, and more.

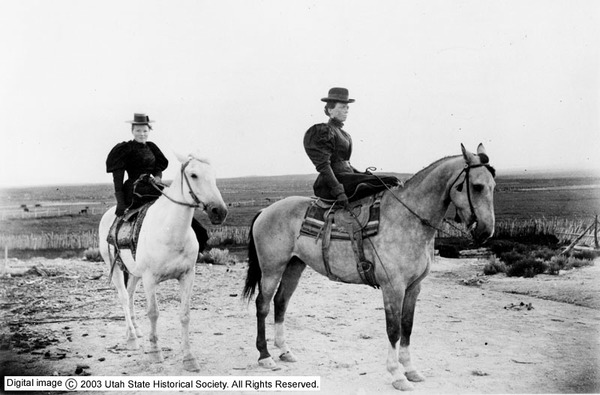

Midwives weren't the only healers on the market. Men called "Thomsonian" doctors could obtain a medical license by paying $20 to Dr. Samuel Thomson, who was a folk healer and popular medical author. But these men were hard to find in rural Utah, where experienced midwives took up the mantle of caring for the ill and traveled widely to share their knowledge. In 1873, the LDS Church Relief Society started a women’s health and hygiene education program, which systematically trained women from every Ward before sending them home to serve their communities. Some, like Hilda Erickson in Tooele County, had to ride twenty-five miles on horseback just to see one patient.

Midwifery teachings blended herbalism, spiritual healing, and practical training to ensure farflung communities had access to medicine. Sagebrush tea was prescribed as a stimulant, milkweed and mud could cure snake bites, and when all medicine seemed to fail, priesthood-holders could bless the sick and wounded. In early Mormonism, women could give blessings during childbirth. A 1915 Relief Society Magazine called midwives the “high priestesses in the chamber of birth.”

As the twentieth century went on, women healers lost legitimacy as the world of medicine professionalized. The male-dominated field of medical obstetrics replaced the popularity of midwifery, Mormon women could no longer give blessings, and doctors stayed in hospitals instead of making house calls. Today, even in the age of tele-health, many rural places do not have easy access to medical facilities and rely on local knowledge -- or even their neighbors -- to care for snake bites, burns, childbirth, and more.

Creator

Source

_______________

See Henry P Plenk, “Medicine in Utah,” Utah Encyclopedia, accessed February 2024; Jenne Erigero Alderks, “Rediscovering the Legacy of Mormon Midwives,” April 3, 2012, Sunstone, accessed February 2024; Karen Kay Jaworski, “Ellis Reynolds Shipp,” Utah Encyclopedia, accessed February 2024; Robert S. McPherson and Mary Lou Mueller, “Divine Duty: Hannah Sorensen and Midwifery in Southeastern Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 65, no: 4 (1997); Becky Bartholomew, “Hilda Anderson Erickson, Working Woman,” March 14, 2016, History Blazer, accessed February 2024.